Books

Books being prepared at the IBE headquarters, Palais Wilson, to be dispatched to POW camps.

1939

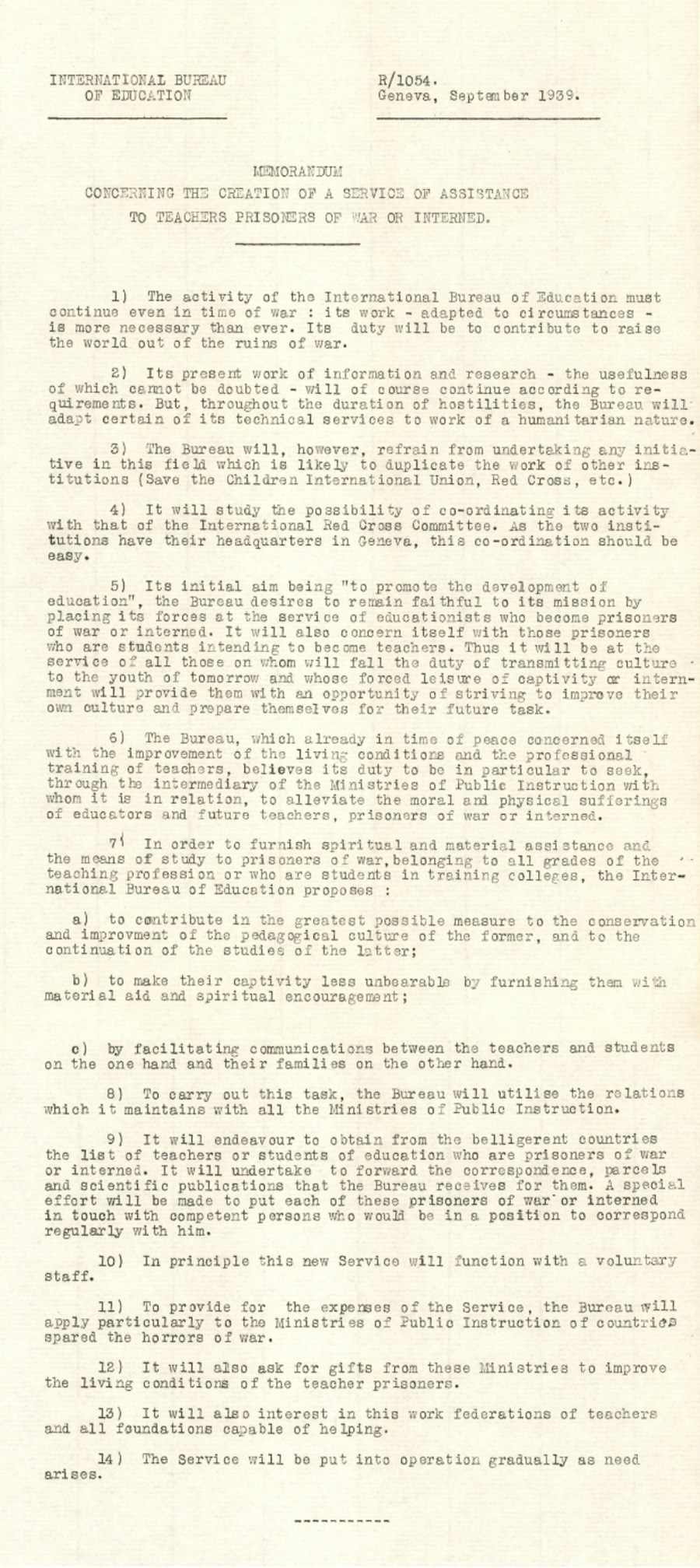

Memorandum

Soon after the start of the war, in September 1939, the IBE Directorate wrote up this memorandum proposing the creation of a “service of assistance to teachers prisoners of war or interned.” The executive committee responded favourably to this proposal soon thereafter. This was the starting point of the IBE’s humanitarian commitment to bring education to POW camps.

1939

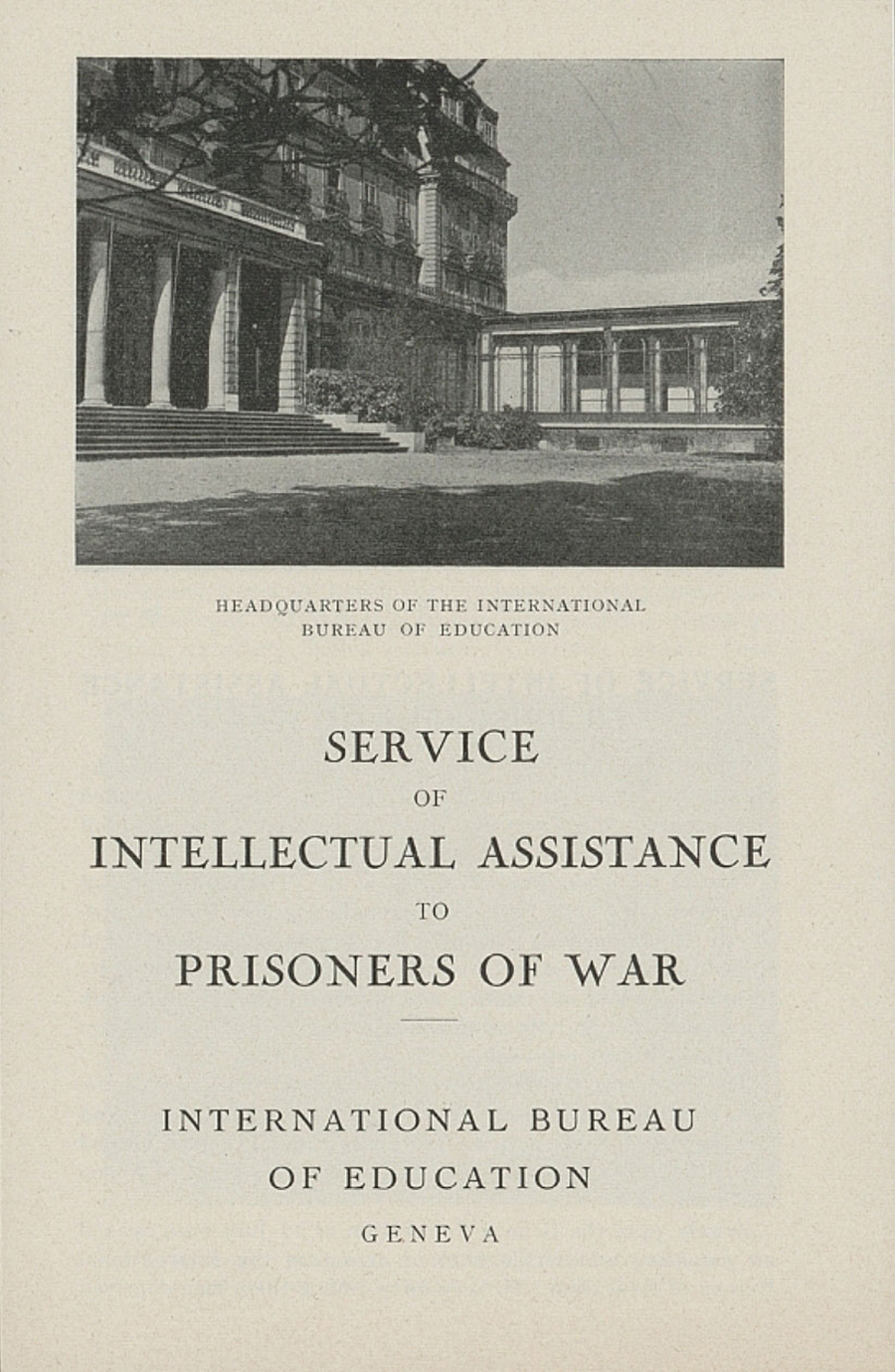

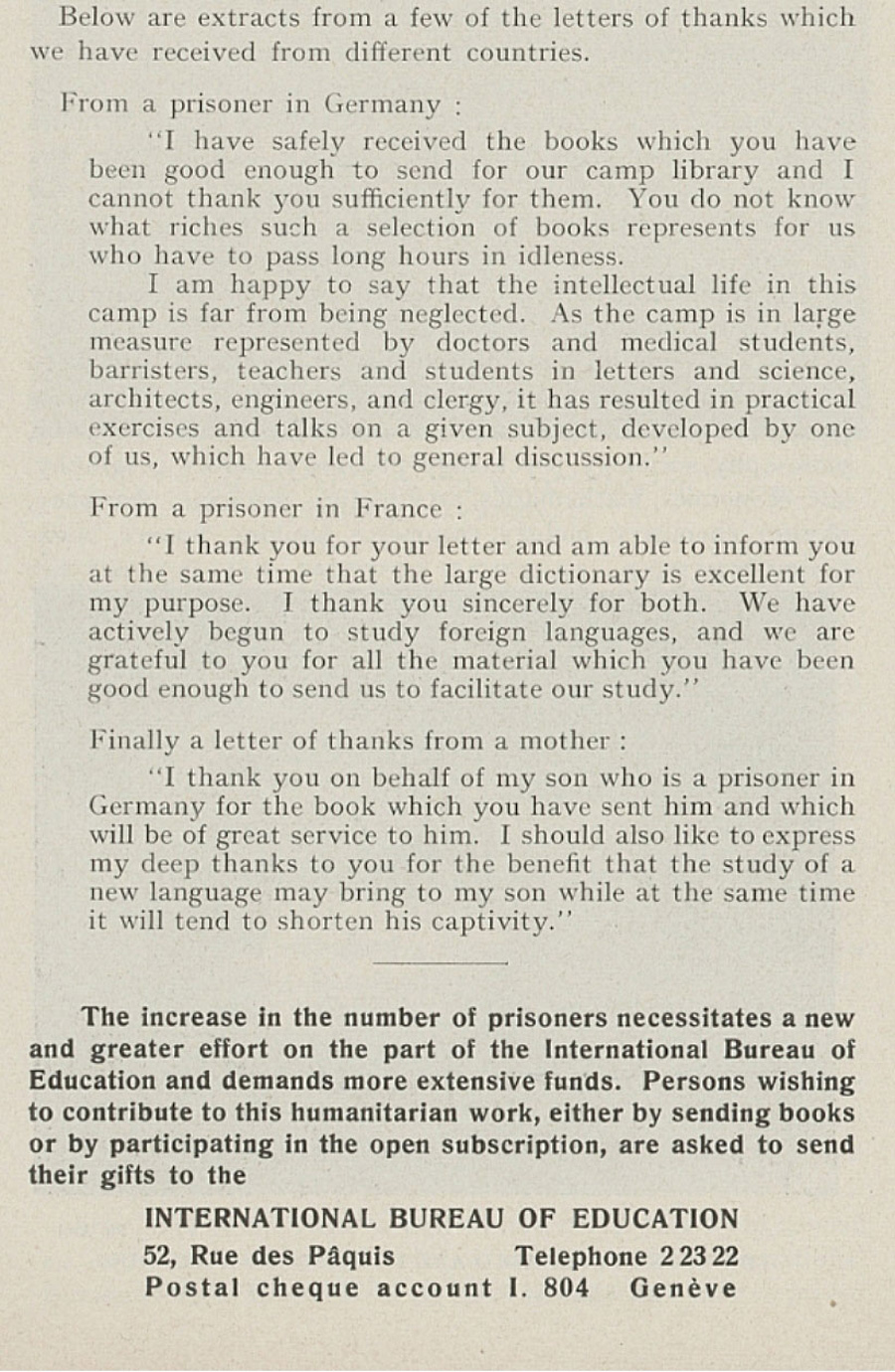

Pamphlet

Excerpts from a pamphlet calling for donations to support IBE’s Service of Intellectual Assistance to Prisoners of War. It contained messages from aid recipients thanking the IBE for their help.

1939

Letter

A letter, dated November 10 1939. In it, the head of the Swiss Federal Political Department Giuseppe Motta confirms to the president of the IBE Executive Committee Adrien Lachenal that Switzerland agreed to contribute a sum of 10000 CHF to the IBE’s intellectual relief service. For Switzerland, IBE’s host state, this was an opportunity to “widen as much as possible its humanitarian action” during the war.

1940

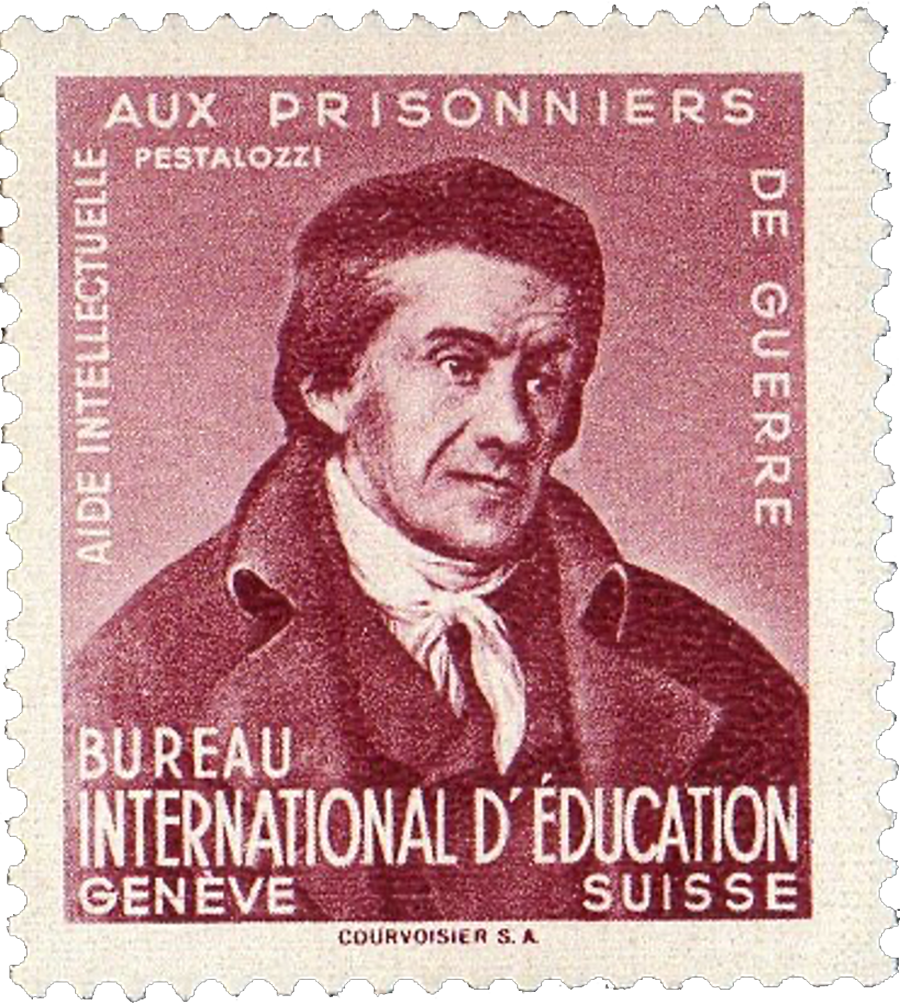

Stamp

The selling of stamps such as this one, depicting Swiss educator Pestalozzi, enabled the IBE to finance its assistance programme to POWs.

1940

IBE staff

IBE staff is preparing parcels of books in 1940 to be sent to POWs. While the Service of Intellectual Assistance to Prisoners of War was headed by IBE’s vice-director Pedro Rosselló, lesser known female employees such as Pernette Champonnière (member of section), Anne Archinard or Madeleine Gysin (both secretaries) made sure behind the scenes that many thousands of requests were answered and up to 600 books were dispatched per day.

1940

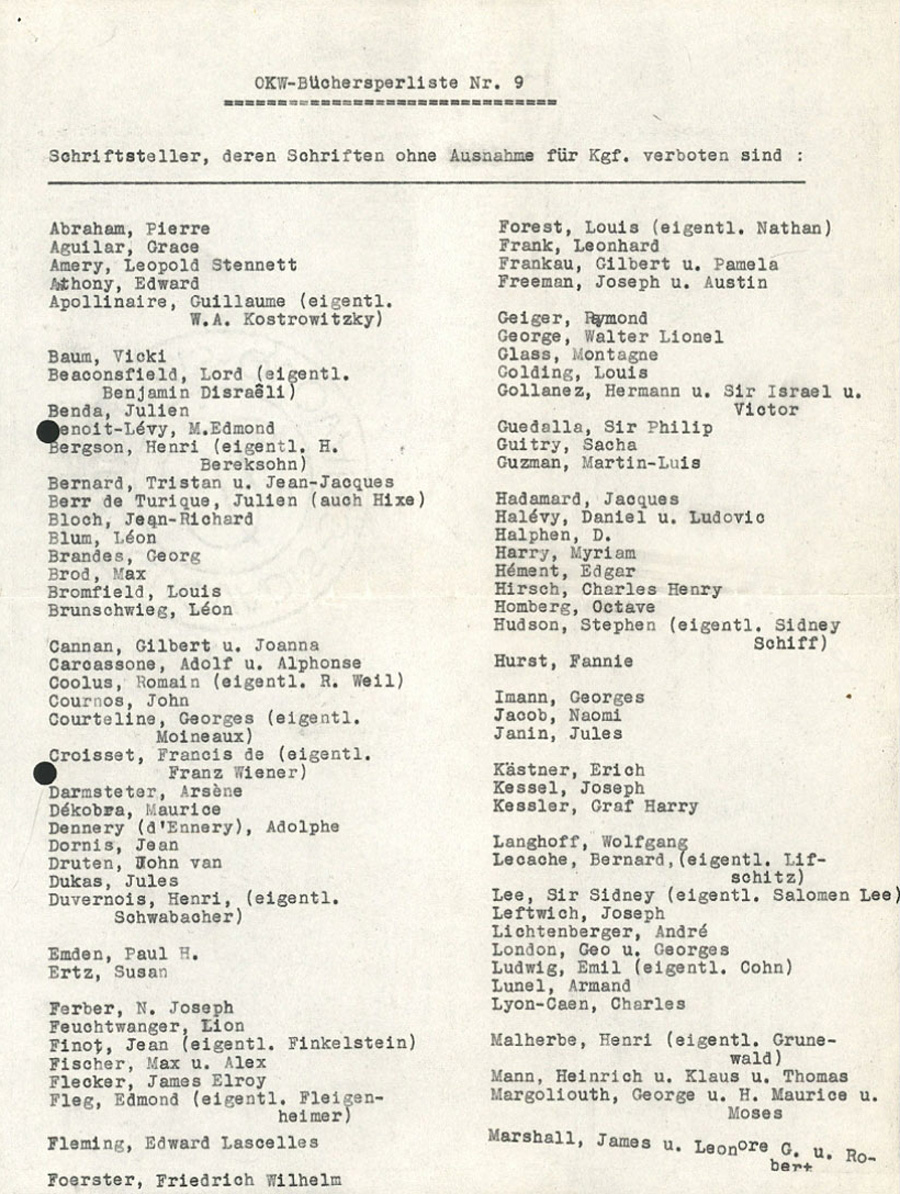

Censorship list

Censorship list by German authorities of banned authors. Books by these writers could not be sent to POWs by the IBE. Besides books by certain – often Jewish – authors, books on issues such as contemporary history, war literature, spying, aeronautical training, radiophony and telephony, pornography, and scouting were also forbidden in German POW camps.

1942 · 1944

Posters

Intellectual aid provided by organisations such as the IBE were vital for the moral and psychological wellbeing of POWs. They usually carried out these activities in the evening after their forced and often exhausting labour was accomplished. Officers were not allowed to work according to the 1929 Geneva Convention, but it was just as important to provide them with occupations. Shown here: the poster of an exhibition on the intellectual, spiritual and social life of POWs in Paris (1944), the cover page of a camp journal in STALAG VII B (1942), and a POW reading.

1940

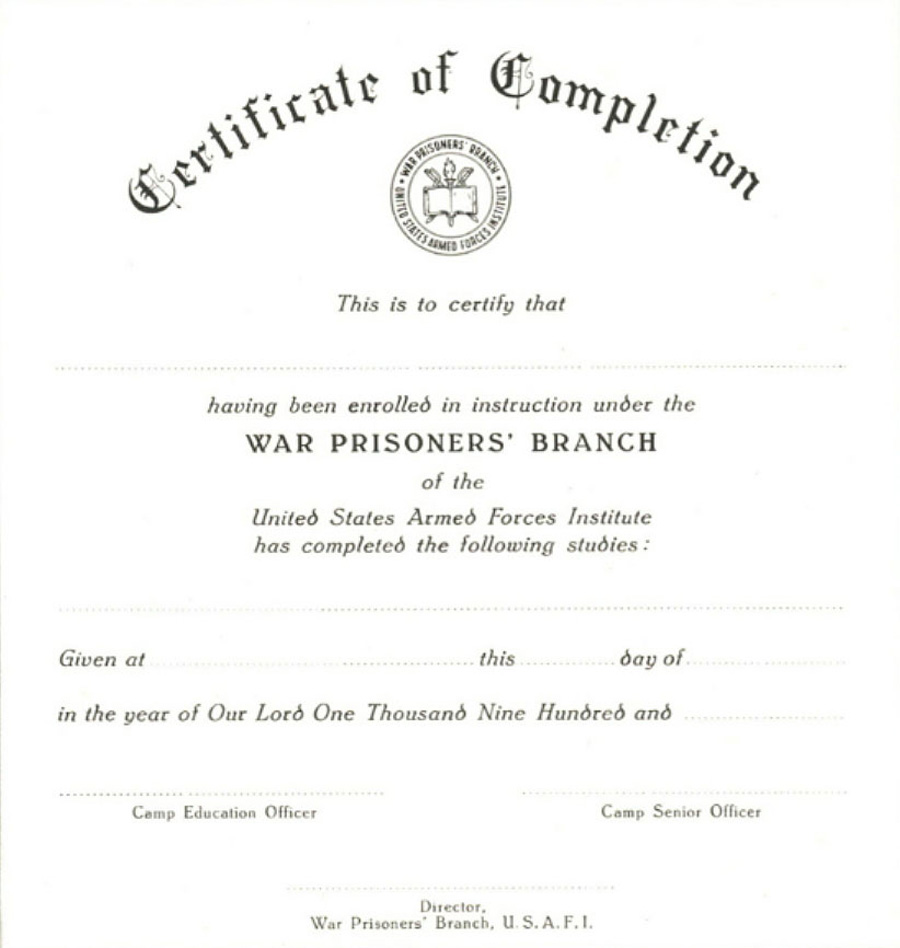

War Prisoners’ Branch of the USAFI

IBE’s point of contact and primary collaborator in the United States was the War Prisoners’ Branch of the United States Armed Forces Institute (USAFI), which created a broad educational program for U.S. soldiers in captivity around the world from high school to college level. These were distance learning courses with regular monitoring. The USAFI commissioned the YMCA in conjunction with the IBE to operate this service for POWs.

1943

Report

Report on educational activities at the German STALAG Luft VI Camp in present-day Lithuania, which the IBE helped to facilitate in cooperation with the British Red Cross Educational Section at Oxford.

1940

The Advisory Committee on Reading Matters for Prisoners

The Advisory Committee on Reading Matters for Prisoners comprised the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA), the International Federation of Library Associations (IFLA), the Ecumenical Commission for the Chaplaincy Service to Prisoners of War, the Swiss Catholic Mission for Prisoners of War, and the IBE. Here it convenes under the chairmanship of Martin Bodmer in the early 1940s.

1945

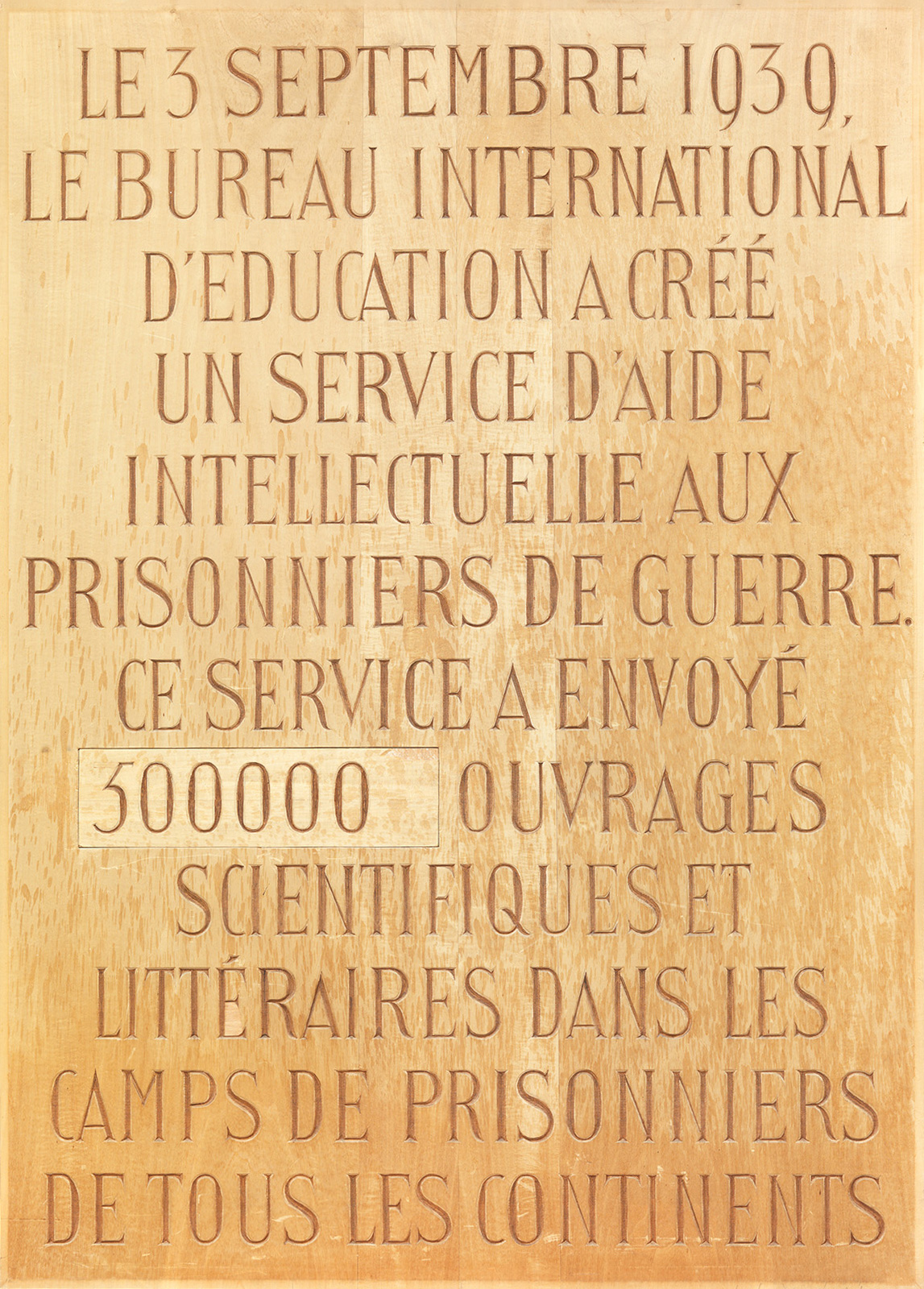

Commemorative plaque

In gratitude, former Belgian POWs of Oflag IIA in Prenzlau, Germany, donated a commemorative plaque after the war, remembering the half a million books sent by the IBE to POWs on all continents.