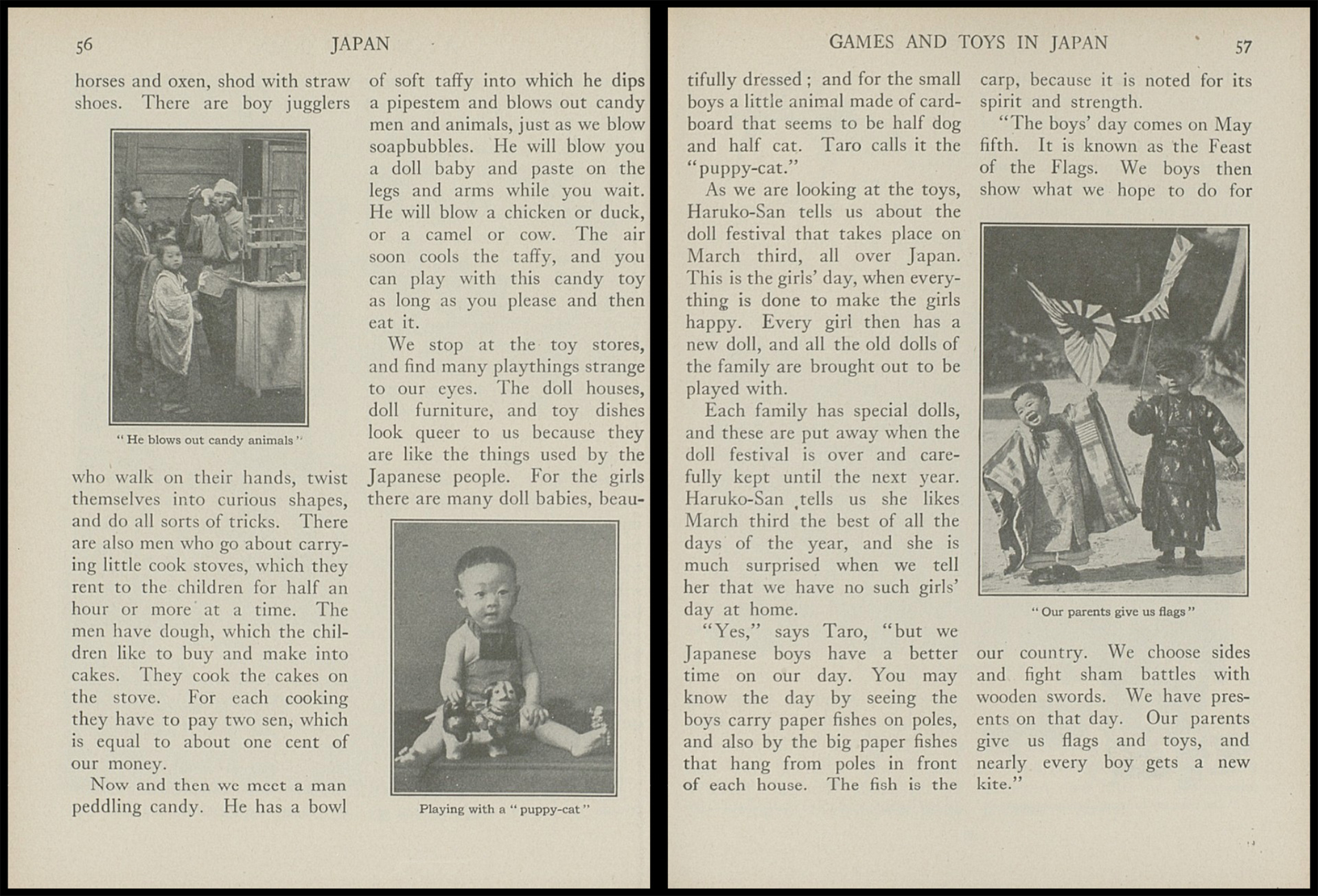

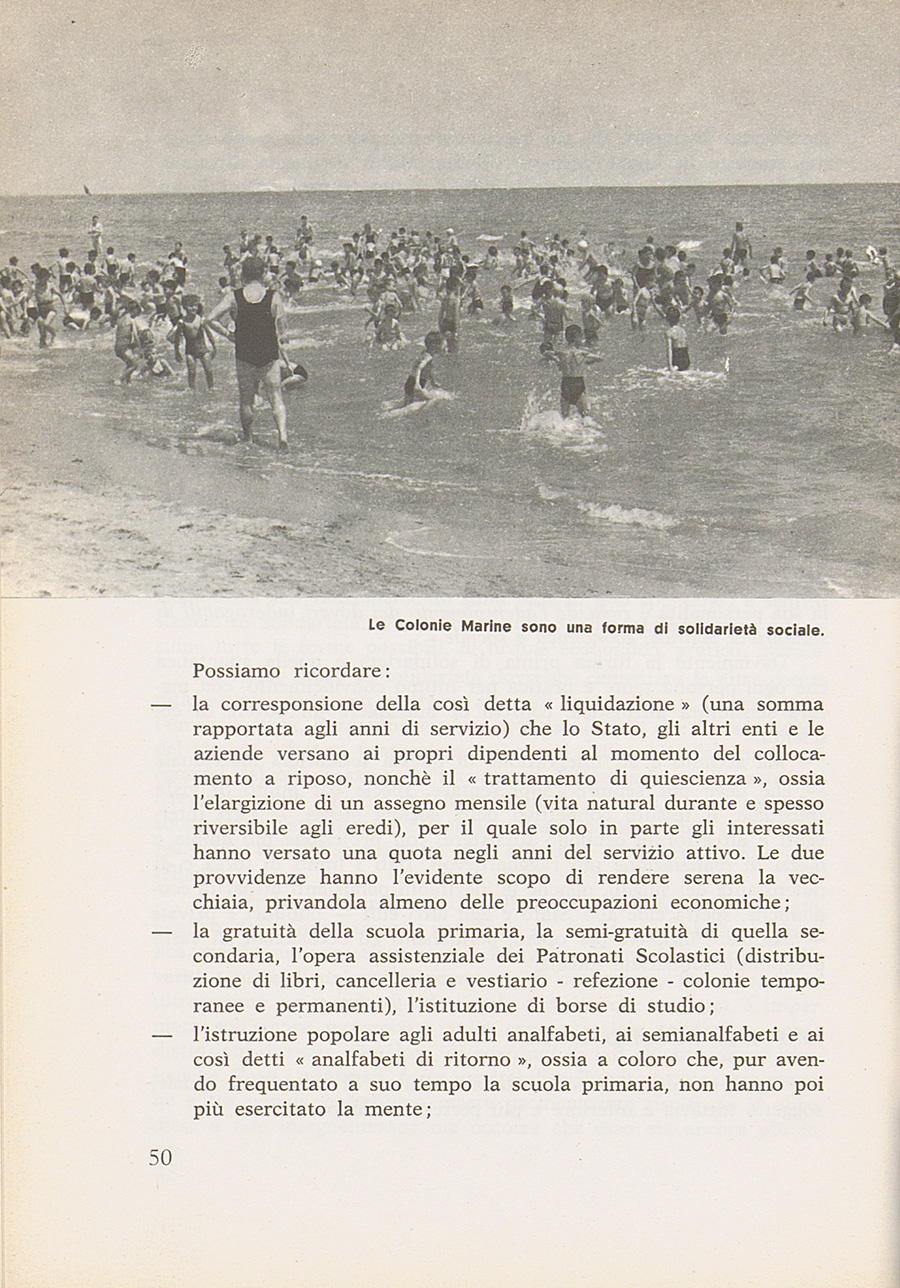

The notion that games and playing in its many forms should constitute an essential aspect of teaching and learning is so pervasive today (see, e.g., the free-play approach to education, the Playful Learning Landscapes initiative, the vision outlined by the Lego Foundation, countless national and local curricula etc.) that one may be inclined to think that this is simply the continuation of a long and steady tradition. That long tradition, however, has quite a zigzagging rather than naturally flowing trajectory. Originally, education and leisurely pursuits went hand in hand; incidentally, the Greek word scholē, which is the ultimate etymon for ‘school’ means ‘leisure’, and the Latin ludus can mean both ‘game’ and ‘school’. It has even been argued that most of the pursuits, rituals and institutions that define civilizations across the globe are essentially forms of play; see, for example, J. Huizinga’s very influential Homo Ludens. More recently, the right to play, as a way of exercising one’s developing capacities and as a reflection of (and means of) the enjoyment of life has been enshrined in a number of seminal documents. The 1990 Convention on the Rights of the Child – adopted by the General Assembly and building on earlier LoN and UN documents – stipulates in article 31 that “States Parties recognize the right of the child to rest and leisure, to engage in play and recreational activities appropriate to the age of the child and to participate freely in cultural life and the arts.”

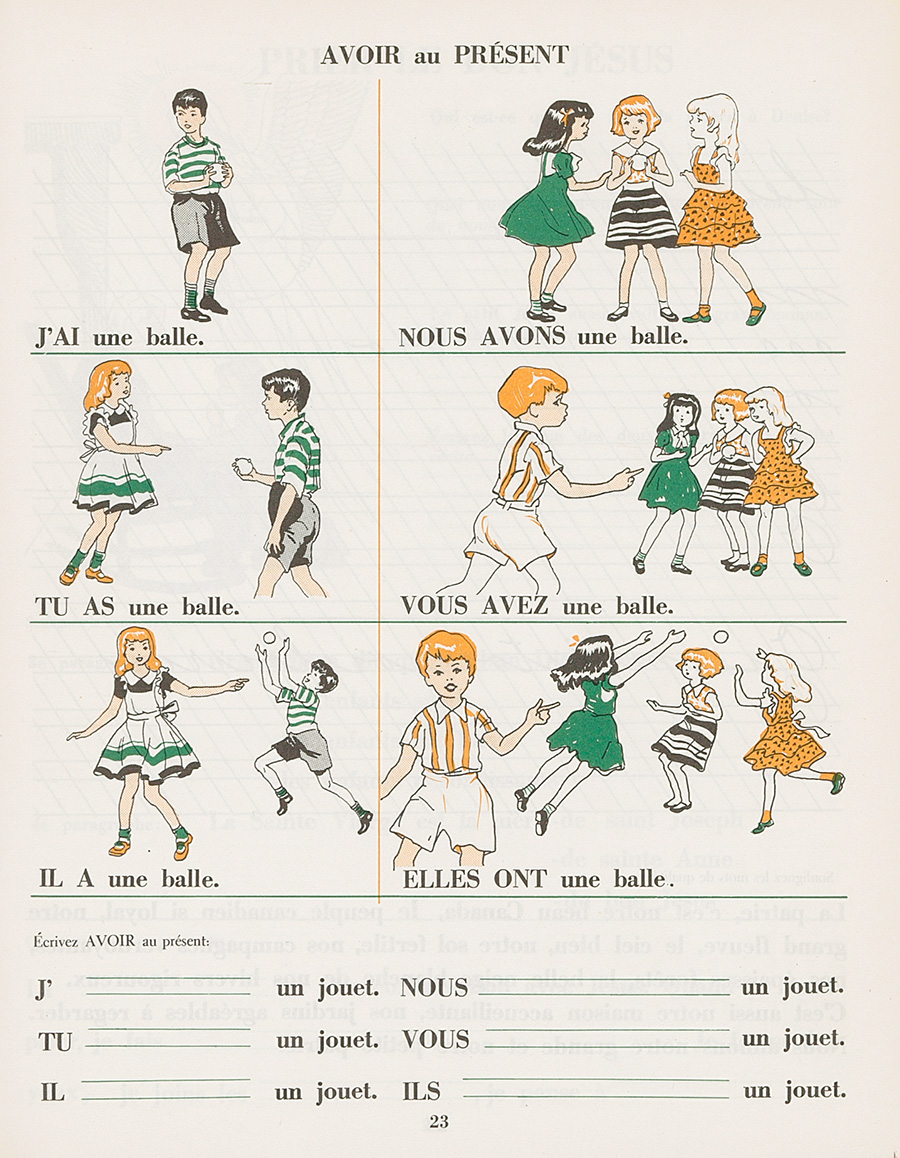

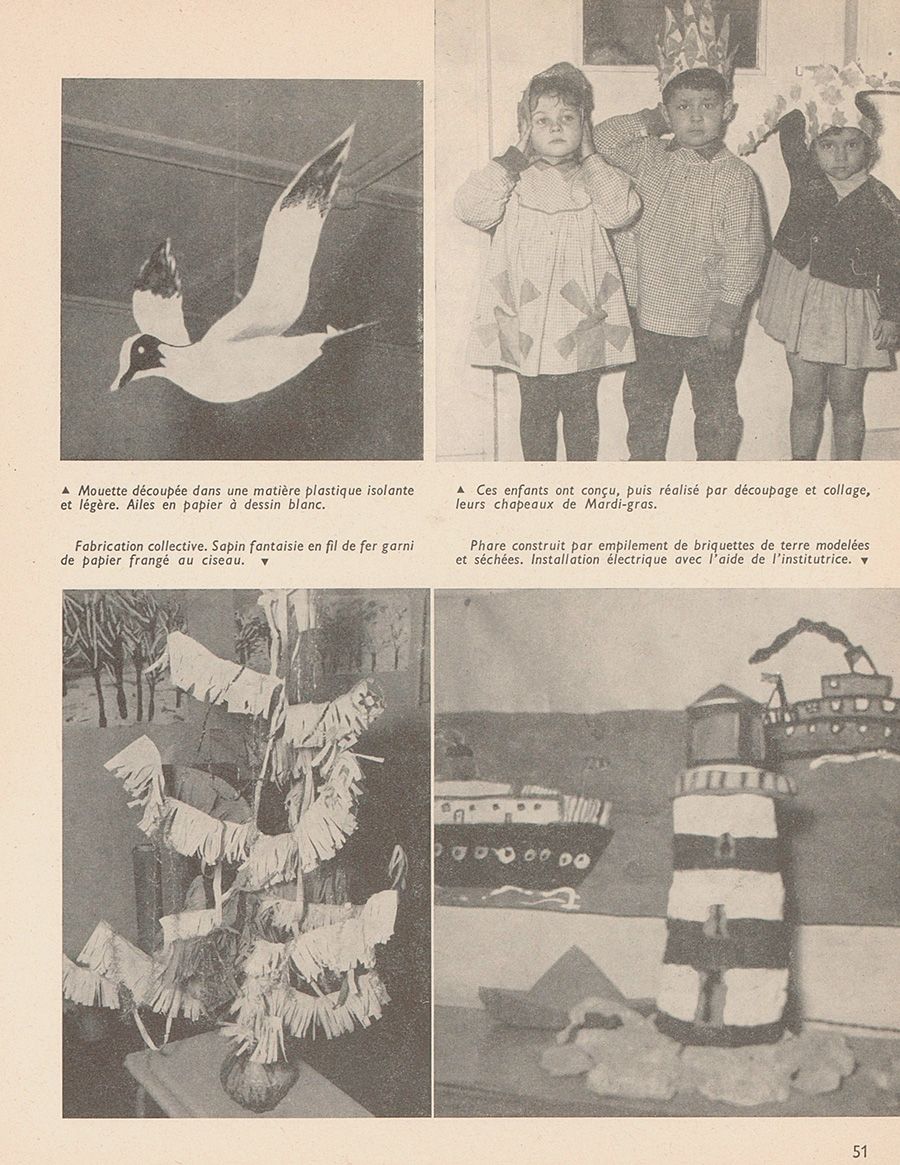

The IBE archive of historical textbooks is an extraordinarily rich source for a survey of this essential aspect of education. It demonstrates in many ways the actual use of games as an instrument for teaching and learning, but also provides interesting reflections – occasionally addressed directly to teachers – on the necessity and significance of incorporating play into the process of learning. The psychological and developmental underpinnings of those reflections and curricular recommendations are sometimes offered in prefaces or other programmatic texts (such as poems which summarize the teachers’ vocations).

There is a fairly clear historical evolution that can be detected in this vast collection. 19th century and very early 20th century handbooks tend to present the material (and the exercises, where applicable) in a fairly stern and, one might say, uninviting manner. We may well assume that in practice teachers would try to make the material more ‘playful’ and accessible, but that is at least the overall impression left by the handbooks themselves.