The history of genre-related distinctions and concepts is as rich as it is complicated and interwoven with cultural, social and political norms and debates. That history, however, is worth more than our archival interest, in so far as it permeates our own social outlooks and aspirations for change right here and now. A country like the United States, for example, which is often taken for granted as a standard of modernity, is currently the place for some of the fiercest debates about gender (and sexuality) with strident demands for changes to textbooks and curricula, with many voices arguing for a return to traditional family values, which are decried in turn by other voices as blatantly discriminatory.

A look at the views advocated by the textbooks in the IBE archives would be thus of much more than purely antiquarian interest and might help us to figure out how we could chart the paths ahead in terms of designing textbooks and curricula. Those textbooks are sometimes arresting in their calls for fresh approaches to gender equality and sometimes perplexing in their stubborn conservatism. The fascinating sources afforded by the IBE are massive, so, for the purpose at hand, we have limited our selection to several textbooks in English (published and / or used in Jamaica, the United States, South Africa, Zimbabwe and Australia), mostly in the 1960s, a decade that witnessed fundamental changes – or at least attempts to bring about changes – in people’s conceptions about family and society. More work remains thus to be done by researchers and, hopefully, by practitioners too.

1939

Joan of Arc

Spaull (1939) reminds young students that valor and selflessness can be found just as much among women as among men.

History for Third Classes (New Syllabus): Stories of Great Men and Women of Many Lands, 1939, by G.T. Spaull; William Brooks, Sydney.

Like other parts of the Commonwealth, Australia designed syllabi that echoed the ‘metropolis’ and were, consequently, steeped in European (and, to some extent, American) history and civilization. This collection of stories, seen as moral exempla, is purported to be comprehensive and balanced, if we are to rely on the title. At a cursory reading, however, it becomes quite clear that exemplary women are just an afterthought for the author, although, admittedly, a very interesting one. Prominent figures like Joan of Arc and Helen Keller cut a truly heroic profile. Heroism obviously comes in many forms, from mystically induced military exploits (Joan of Arc) to being a champion for the disadvantaged and marginalized (Hellen Keller). Keller’s determination to overcome apparently insurmountable vicissitudes and to help others through her selfless and unflagging support of disability rights is a memorable portrait (in two panels, two short sections of this volume), even if one wishes that more such heroines had been portrayed here.

1939

Helen Keller

Spaull (1939) distinguishes between different types of heroism, including the determined fight for disability rights.

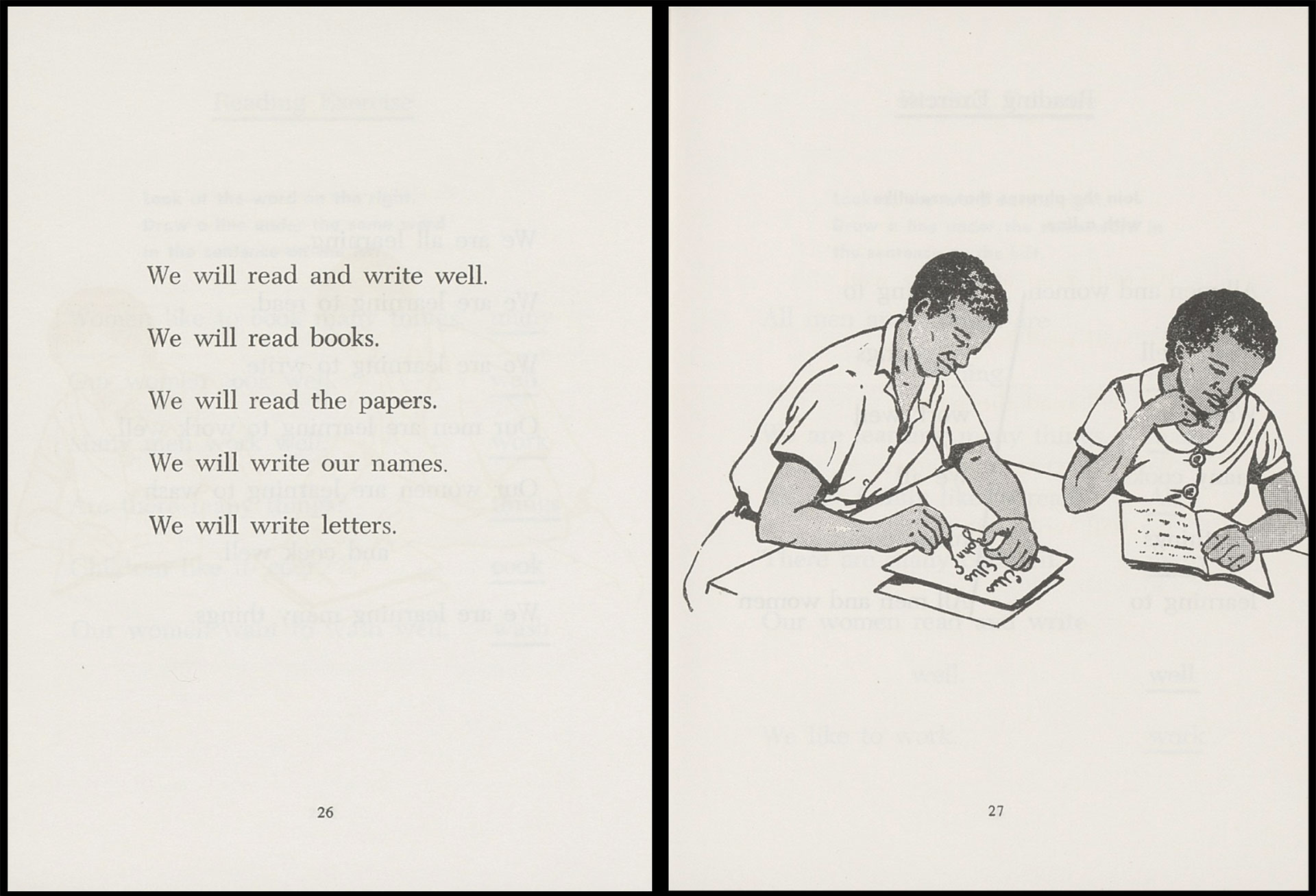

Our Class and Our Family: A Pre-Primer, 1962, by Enid de Casseres and Marjorie Kirlew, published by the Literacy Section of the Jamaica Social Welfare Commission, Kingston.

This textbook is an adaptation for Jamaica’s social and educational needs, based on Our Class by Ella Washington Griffin (a UNESCO consultant). The year of publication is not to overlook: Jamaica secured its independence in 1962, so this publication reflects in part the authors’ vision (and presumably also the program of the Jamaica Social Welfare Commission) for the future of Jamaican society. One should add that, given the publication of this textbook under the aegis of an organization charged with overcoming illiteracy, we can safely surmise that it is meant not just for children, but also for adults. This book relays in some measure a division of labor (and a social hierarchy) still supported by European and American curricula in the 1950s and early 1960s, with women depicted as willingly, if not eagerly, learning to cook and wash, while men are assumed to embark on various careers and become breadwinners. It’s notable, however, that the illustration focusing on the benefits of learning to read and write displays both a man and a woman, making no gender distinction when it comes to the right to (and need for) education.

1962

De Casseres and Kirlew (1962)

Traditional values for a new Jamaica.

1962

De Casseres and Kirlew (1962)

Both women and men deserve to enjoy the fruits of education.

Families and Their Needs, 1966, by Edna A. Anderson; Silver Bourdett, Morristown, USA.

Our Working World: Families at Work, 1964, by Lawrence Senesh; Science Research Associates, Chicago.

Gender roles or the absence thereof form a topic that, in the view of authors like Edna A. Anderson, should not be relegated strictly to textbooks for middle schools and high schools. This lavishly illustrated and eminently readable textbook for primary schools is meant to help the young students think about the fundamental aspects of families across cultures and continents. Instead of preaching gender equality in explicit and potentially uninspired or uninspiring ways, the author conveys some of her main points implicitly, and thus more effectively, through photos and drawings that illustrate the fact that women and men (as well as girls and boys) should participate in many and often interchangeable ways in the structure and lives of their families.

1966

Anderson (1966)

Learning to ignore discriminatory occupational boundaries from a very young age.

For example, a photo of two girls preparing to bake biscuits together with a boy of similar age (their brother?) seems intended to dispel various domestic – and other – prejudices. Photos placed on opposite pages and representing female and male physicians or women and men equally engaged in the textile and fashion industry and performing comparable, if not identical, duties, are supposed to encourage reflection on the students’ own families and on their own opportunities and possible future careers and vocations. It is probably relevant that this book was published in the mid-1960s in the United States, a time and place for a radical reconsideration of gender roles (although, admittedly, that period marked only one stage in that reconsideration, a process that is still very much going on in the USA and elsewhere). The overall approach adopted in Anderson’s book is articulated plainly in the teacher’s edition, which accompanies it.

1966

Anderson (1966)

Women have just as much to contribute to the fashion industry as men do.

Lawrence Senesh’s book too is addressed to elementary school students (and largely dispenses with text in the first chapters), embracing a participative approach to understanding the central needs of families and the distribution of duties. Children – girls and boys alike – are encouraged to join family activities, including domestic chores. Furthermore, a comparison between different cultures (bushmen, Eskimos etc.) reveals that despite notable differences, key elements – such as women’s and men’s joint participation in ensuring the success and thriving of their families – are virtually universal. It’s interesting, though, that the image portraying a typical ‘western’ family suggests that the father is expected to have gainful employment, while the mother stays at home with the children and happily cooks away! So much for the revolutionary 1960s?

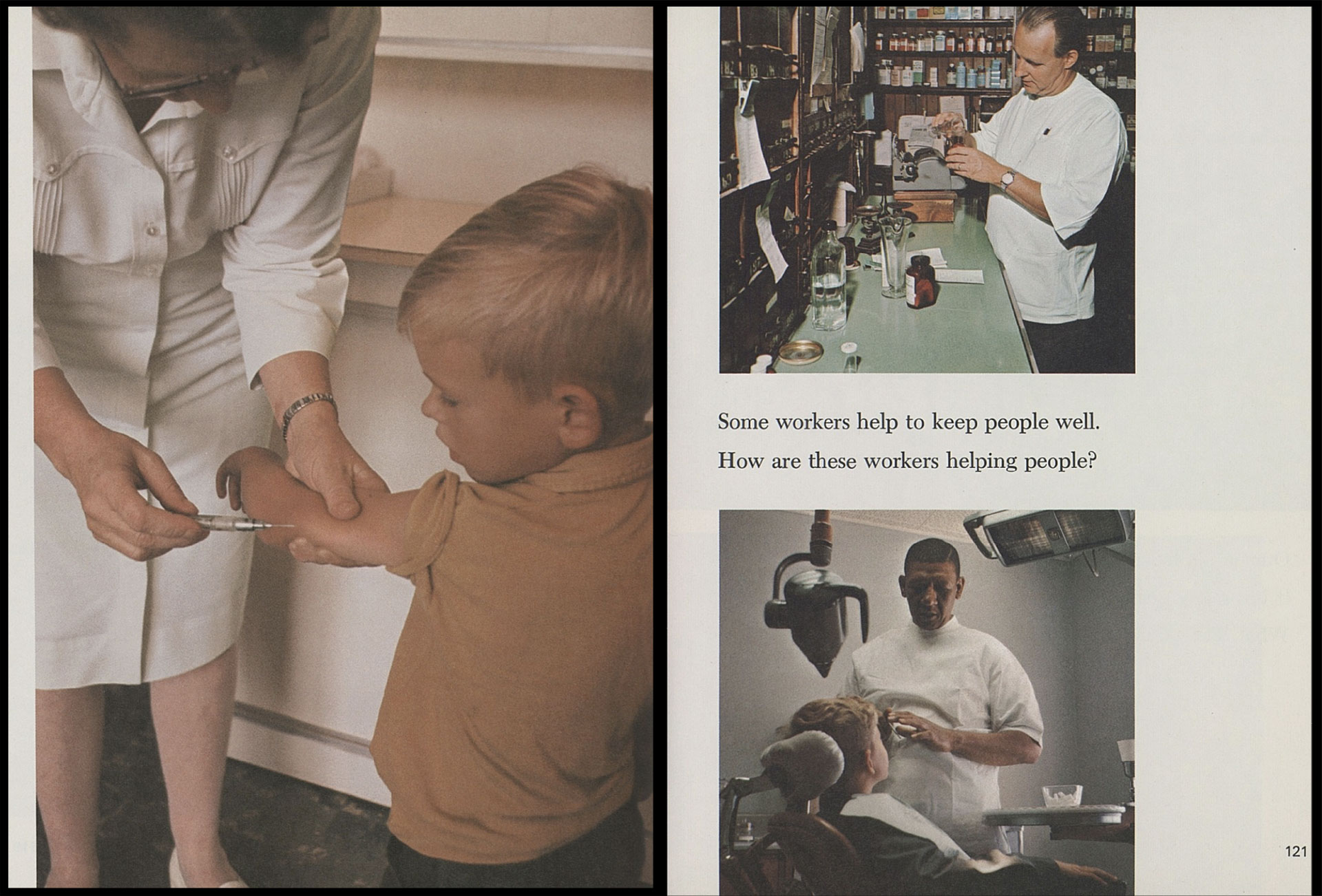

1966

Anderson (1966)

Female and male physicians, nurses, dentists – equally talented, equally helpful.

1964

Senesh (1964)

Equal participation of spouses in supporting their families, but in roles that replicate old preconceptions.

Domestic Science Textbook (2nd ed.), 1965, by R. Fouché and D.K. Selkirk; Longmans, Cape Town.

How to Wash and Iron Things for Your Family, 1961, by D. Cartwright (education officer); Longmans (in association with The Northern Rhodesia and Nyasaland Publications Bureau), Johannesburg and Salisbury.

Judging by the references to primary school education (the authors assume that their readers are by now familiar with more basic notions and methods), Domestic Science Textbook seems intended for middle schools and potentially for high schools as well. To say that the approach adopted here is patriarchal would be a mild understatement. There is no hesitation in assigning virtually all conceivable housekeeping tasks to women. Indeed, the domestic encyclopedic knowledge that housewives are supposed to master underlies an entire constellation of presumed virtues, i.e. of what a morally commendable wife is expected to embody. The quasi-scientific language and level of detail in the chapters of this textbook seem to imply a sort of logical necessity for the gender roles marked out here. Cooperation from other members of the family is not discounted, but securing such support is also one of the housewife’s duties. It should be noted that, given the nature of the illustrations, this is also rather clearly a subtle nod to the apartheid regime: the technologically and socially sophisticated picture of the domestic space appears to be – primarily or exclusively – that of white families in South Africa.

1965

Fouché and Selkirk (1965)

Patriarchal division of labor in white South African families.

Speaking of the lingering impact of the colonial powers, D. Cartwright’s How to Wash and Iron Things for Your Family is intended for the local population of Rhodesia (today’s Zimbabwe) and, while this is overtly an education book, generally understood, it does not appear to have been exactly a schoolbook. Be that as it may, one cannot miss the fact that its intended audience or readership consists strictly of women from the indigenous population, as the illustrations indicate. It is also hard to disentangle the purported good intentions of the author from a certain pervasive sense of condescension.

The fact that some of these books are authored by women and some by men (or both) does not seem to influence the views conveyed on the social and professional standing of men and women in modern society. Both women and men are perfectly capable of doing exceptional work as agents of change for greater equality or, on the contrary, of perpetuating problematic and discriminatory views anchored in a deep and complex history. The many connections between gender distinctions and representation, and between gender (in)equality and decolonization, among other things, make these books a treasure for anyone interested in the history of curricula, and, indeed, interested in the future of curricula as well.

1961

Cartwright (1961)

Helping indigenous families, while entrenching occupational distinctions between men and women.