It may be a truism – but one that’s very much worth uttering and pondering – that education is one of the most potent tools in fashioning attitudes, characters and in directing action, for better or worse. This is particularly the case when it comes to promoting patriotism or cultivating nationalism of various brands. Even in peaceful times, it may be hard to define the identity of a people with any measure of precision, given its possible cultural overlap with neighboring nations or the impact of globalization etc. It may be an arduous task, but it is about as important as it gets. A clear sense of national identity can be truly a necessary (though rarely a sufficient) condition for the success of a nation, especially in periods of upheaval, after securing independence, whether in the wake of colonialism or following the disintegration of larger states (the Soviet Union, Yugoslavia etc.). A factor that we find of special interest in surveying various textbooks from the extremely valuable collection of the International Bureau of Education is the very selection of the aspects that are taken to be defining markers of a collective national portrait.

In some cases, cultural heritage (from folklore to architecture), typical social institutions and moral norms, religious traditions, and language will do. In other cases, designers of curricula and authors of textbooks appeal to other factors as well: they add ideological ingredients that, they claim, become not just important, but vital in outlining a nation’s identity. This tends to be considerably more the case with totalitarian regimes than with democracies. The educational and ideological landscape we are attempting to sketch here is chiefly an implicit comparison between the way in which students are invited to reflect on what it means to belong to their nations in democracies (as in most of today’s curricula), on the one hand, and in totalitarian states, on the other (e.g., fascist Italy and Romania under communism – the two cases under scrutiny in this analysis). This outline can also serve potentially as a starting point for further research on the distinction between patriotism and nationalism, as revealed in IBE’s important collection of textbooks.

1963

Bistriteanu et al. (1963)

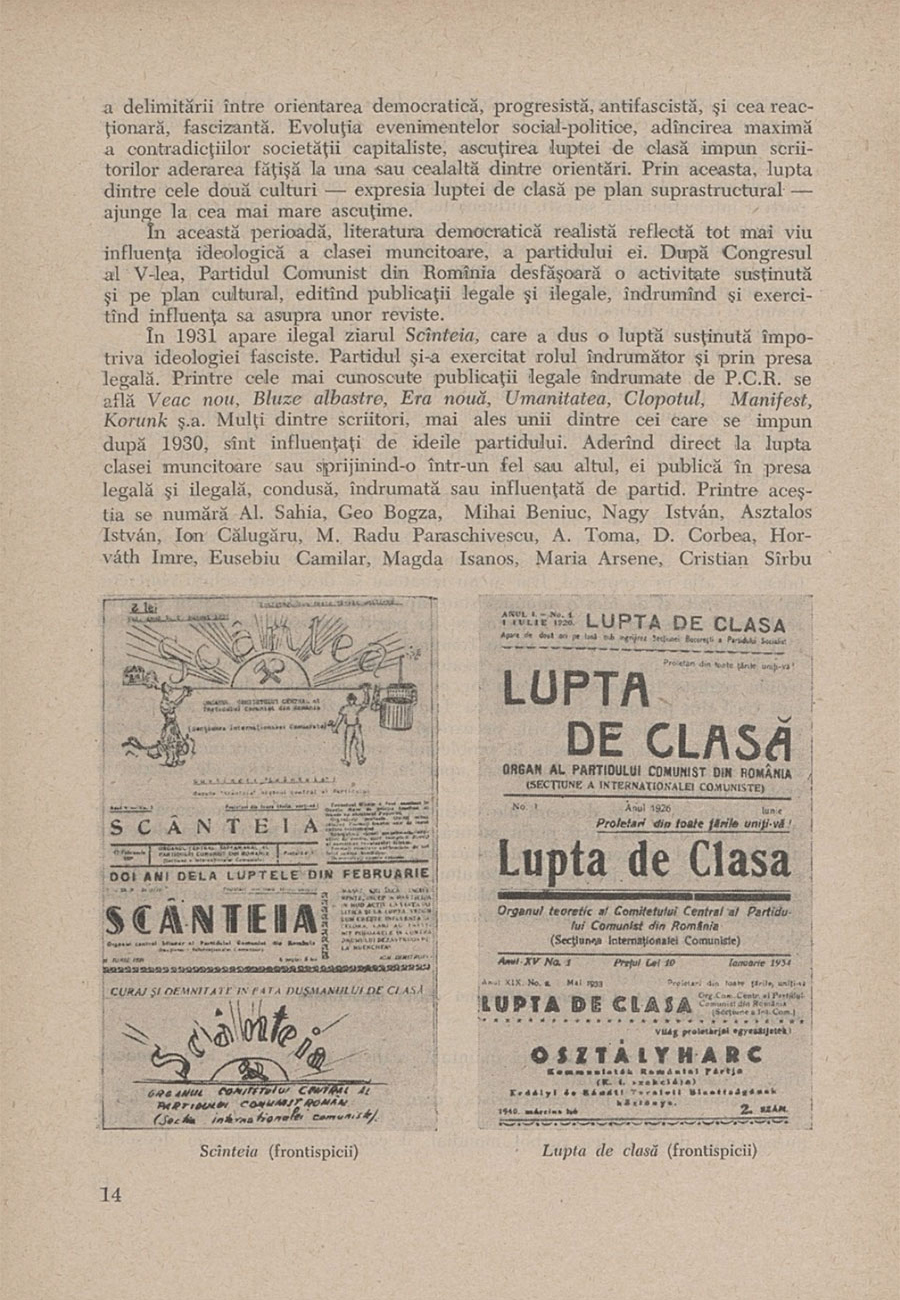

A ‘prehistory’ of Romanian communism through the study of pre-World War II periodicals is intended to leave the impression that much of the contemporary Romanian literature (even before the war) was infused with a communist message and aura.

Literatura Românā Contemporanā (Contemporary Romanian Literature), 1963, by Alexandru Bistriteanu et al; Editura didacticǎ şi pedagogicǎ, Bucharest.

Limba Romana, manual pentru clasa a III-a (Romanian Language, textbook for 3rd grade), 1968, by I. Berca, D. Goga and E. Utā; Editura didacticǎ şi pedagogicǎ, Bucharest.

What might a reader expect in the opening sections of A. Bistriteanu’s (et al.) literature textbook for middle schools and high schools? A fine and detailed distinction between dominant literary trends, a discussion about the evolution of genres and the formulation of new narrative techniques or stylistic manifestos? If so, one would be in for a bit of a shock. The authors are rather interested in situating all the major contemporary Romanian writers discussed here in the context of the clash between opposing ideologies: the ‘exploiting bourgeois’ camp and the relatively new and liberating communist ideology that, the authors assure us, will shatter the shackles of exploitation once and for all. It should be noted that 1963 is an interesting point in the history of the Socialist Republic of Romania. The years of open and rampant Stalinist repression are drawing to a close, as the middle of that that decade is about to usher in an apparently more ‘humane’ version of communism (its purported humaneness will soon

1968

Berca et al. (1968)

Ancient and medieval history are marshalled in the service of a decidedly communist approach to patriotism, or rather nationalism.

This ideological polarity forces the student to reconsider through a political lens virtually all the literary merits of the Romanian writers, not just belonging to the post-war period, but also of those authors who came to prominence before World War II. To make this distortion easier to accept, the authors of this textbook deal at some length with periodicals which had more to do with the rise of the communist movement and less with literature in the 1920s and 1930, including publications with telling titles such as Scânteia (The Spark, which would later become the main newspaper and the most effective mouthpiece of the RCP), Bluze Albastre (Blue Shirts), Lupta de Clasā (Class Struggle) and Veac Nou (New Era). The intended point is that some members of the Romanian intelligentsia between WW I and WW II published in some of those periodicals, and that provides the key to evaluating their literary works; a rather flimsy connection at best. Discussing those journals and newspapers in this context generates the illusion that the worth of a nation’s literature and literary language is indissolubly linked with politics. That is, with the political demands of a communist movement apparently invested in the prosperity of an entire nation, but in fact interested mostly in its self-perpetuation and self-promotion.

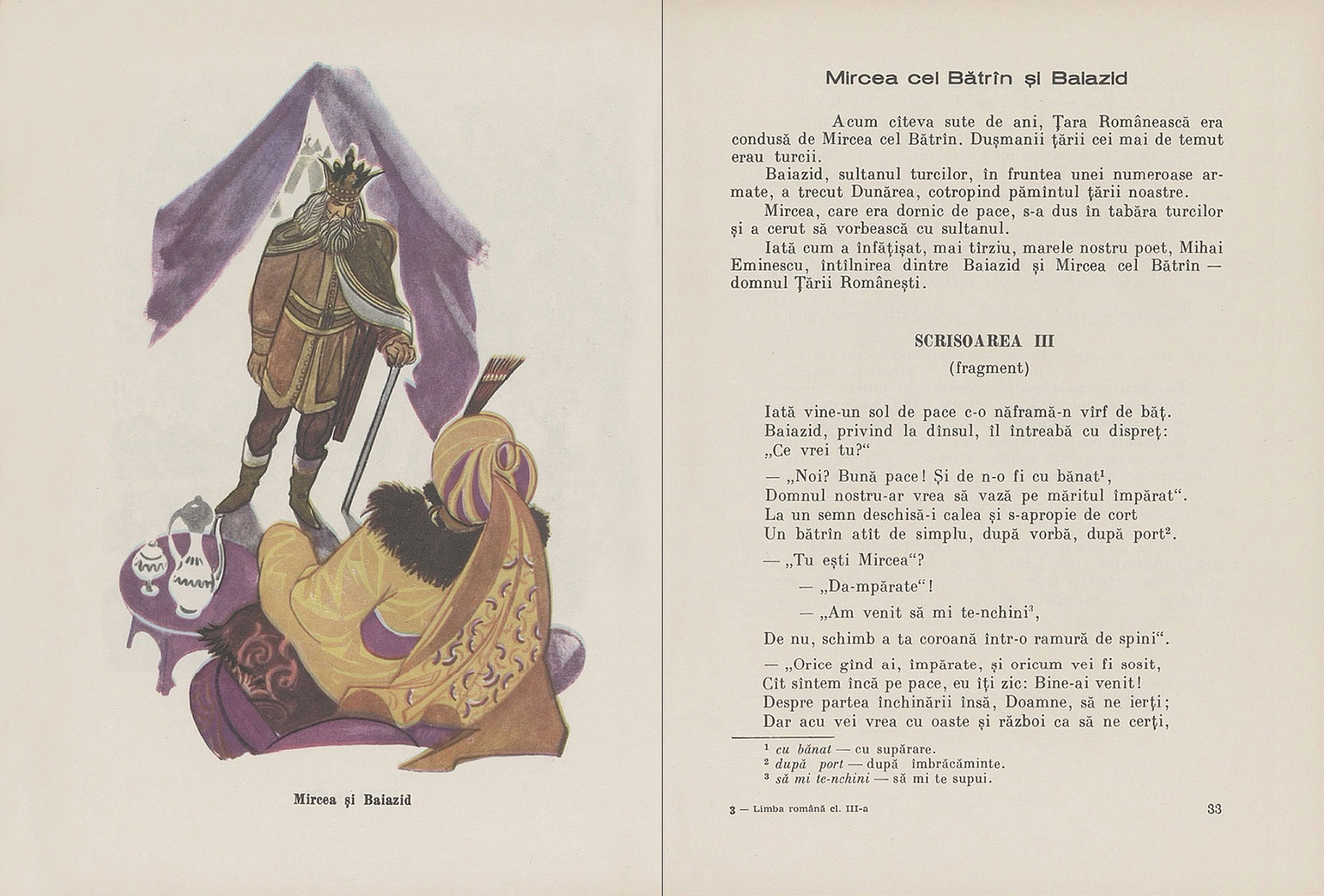

It’s also noteworthy that the communist regime did its best to muster more than just a few decades of history in its attempt to redefine the Romanian national identity. History textbooks as well as Romanian language textbooks vouch for that. In Berca et al. (1968), for example, one of the stories told for the sake of improving reading skills in elementary schools extols the glory of the ancient Dacian people. One might think that glorifying the Romans would be a more sensible way to emphasize the nature of Romanian, a Romance language, but the communist regime, especially since 1965 (under N. Ceausescu), was keen on reinventing the Romanian cultural DNA, so to speak, and to promote a particular type of nationalism and autochthonous identity by stressing the richness of the Thracian / Dacian substrate (incidentally, only a handful of words presumed to be Dacian survive in Romanian). Medieval history too is put to work in a similar way, with the selection of passages from major Romanian authors (e.g., M. Eminescu, deemed Romania’s ‘national poet’) which praise the exploits of Romanian princes or ‘voivodes’ in their struggle against the Ottoman invasion. All of those historical episodes, however, point to ideals cherished by the communists in power – e.g., self-determination, keeping a proper distance both from Moscow and from the West etc. – and help to mix a strange cocktail of national and ideological values in an effort to refashion Romania’s national identity through the education of current and future generations.

1937

Fanciulli (1937)

Natural and architectural beauty can be enjoyed by the young readers of that book, according to the author, in part because such beauty is protected and somehow enhanced by Mussolini, as the book’s dedication points out clearly and quite unctuously.

Glorie d’Italia: libro per la goventù Italiana sotto ogni cielo (Italy’s Glories: A Book for the Italian Youth from Everywhere), 1937, by Giuseppe Fanciulli; Società Editrice Internazionale, Turin.

Bella Italia, amate sponde (Beautiful Italy, Beloved Shores), 1930, by Orio Vergani, Fondazione Nazionale del Littorio, Rome.

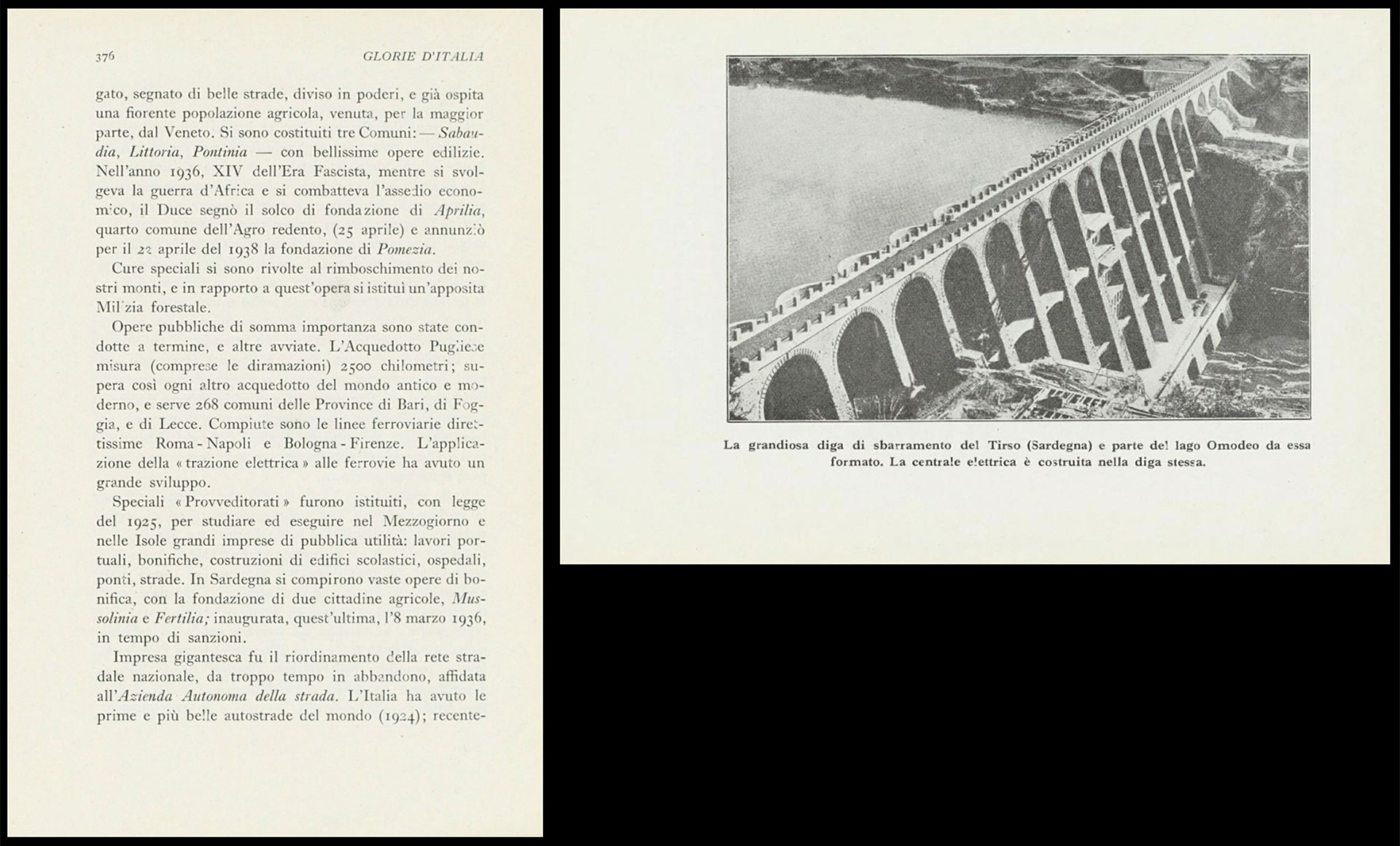

Fanciulli’s Glories of Italy (1937) is expressly addressed to the Italian youth from everywhere (“under every sky”, sotto ogni cielo). No one can say reasonably that Italy is not an extraordinary land in terms of both natural beauty and countless examples of glorious culture. The way in which those wonders are presented in Fanciulli’s book, however, should give us pause. Everything, from the charm of the Amalfi Coast to the Romans’ conquests, to Dante’s poetry, to Galileo’s discoveries and to the unification of Italy in the 19th century – all of that and everything in between and beyond is perceived and glorified from the angle of fascism (at its peak in the pre-war years). From the outset, the book is dedicated, “with an Italian soul full of admiration and devotion”, to Mussolini “who protects and renews” the glories of Italy. A few hundreds of pages later, the very last line, in an epilogue about the expected future glory of the Italians, reads in translation: “Oh God, may you protect Italy and its Leader now and forever.”

1937

Fanciulli (1937)

A photo of Addis Ababa might seem out of place in a book about the beauty of Italy, if it weren’t for fascist Italy’s expansionism, purportedly a natural continuation of the glory of ancient Rome.

We know that the prayer was not exactly fulfilled, at least with respect to Italy’s fascist leader, but the more interesting aspect is how the beginning and the end, and also numerous remarks in the body of this book, convert all the many grounds for the Italians’ genuine claims to national pride into a pretext to ‘educate’ the Italian youth in a way that conforms closely to the fascist ideology and to Mussolini’s cult of personality. Moreover, the tone of several chapters assumes a messianic ring: our nation has been blessed with so many triumphs and so much beauty so that it might culminate with this episode of economic success and military conquest (that is, the massacres in Ethiopia) and to serve as an exemplum to other nations (which, unfortunately, it did indeed: Nazi Germany was certainly emboldened by what had happened in Italy). Imperialism plays an outsize role in this context, as the author lionizes several generals who had led a murderous campaign in Ethiopia. Young students, then, are likely to mix historical figures like Garibaldi and Vittorio Emanuele II with the likes of Mussolini and his clique, and to confuse patriotism with militant nationalism, and cultural glory with an extremist ideology.

1949

Fanciulli (1937)

A photo of Addis Ababa might seem out of place in a book about the beauty of Italy, if it weren’t for fascist Italy’s expansionism, purportedly a natural continuation of the glory of ancient Rome.

Even in earlier years, Italian authors of textbooks for elementary and middle schools were going out of their way to deepen this confusion. Vergani’s 1930 book is basically a long poem to “Bella Italia” and its beloved shores. It starts, however, not surprisingly, with a quote from Mussolini, who glorifies “divine” Italy. An element shared with Fanciulli’s description of the Italian ethos is the emphasis placed on the Catholic faith (debates continue to this day, of course, about the extent to which the Vatican was serving Mussolini’s interests in the 1930s and in the early 1940s). Besides the many illustrations underlying this praise of the Italian spirit, seen through a fascist prism, the map placed at the end of the book also deserves our attention. It shows not just what we would recognize today as Italy, including its islands, but also a goodly chunk of North Africa. That undoubtedly foreshadowed Italy’s expansionist ambitions in Libya, where, as in Ethiopia, fascist Italy was responsible of massacres and where it ruled over a colony – Italian Libya – between 1934 and 1943. Again, ruthless imperialism purportedly becomes part and parcel of what it means to be an Italian.

1930

Vergani (1930)

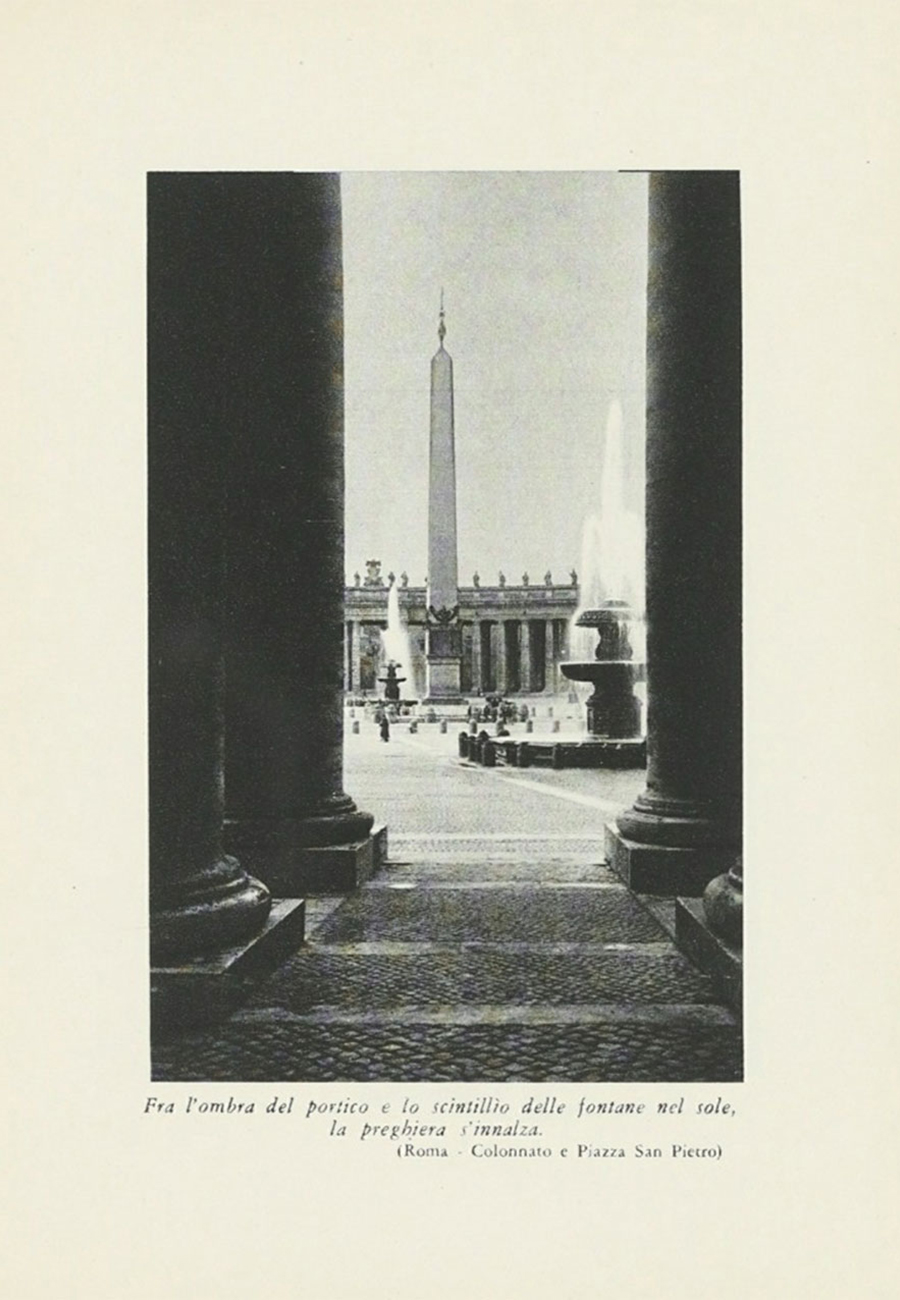

The majestic beauty of the Eternal City seems to echo its ancient imperial strength and thus the entitlement to dominating other lands and to submitting its own citizens to a rigorous ideological discipline.

We can read these and many other books from the IBE collection with great historical interest, but let’s pause for a second and put ourselves in the shoes of the students who were actually using such textbooks in their respective schools and who were the primary target of this subtle propaganda. One indication that such curricula were not ignored or were not simply received with cynicism by students may be that many Italians after World War II and many Romanians after the fall of communism in 1989 continued to defend a sense of patriotism, if not nationalism, that was partly defined by the ideological seeds sown earlier in such textbooks for decades. We can take this as a warning that clear discernment and the cultivation of truth are essential to the sort of democratic and just societies in which we wish our children to grow up. And, with the widespread relativization of truth and also the rise of populist regimes, this may be a more urgent task than it has been in decades.

1930

Vergani (1930)

Catholicism is presented as a fundamental aspect of the Italian ethos, a problem for those Italians who were not Catholic or particularly religious.