To say that the past is no more and the future is not yet is a convenient truism often meant to encourage us to make the most of the immediate present. And yet this schematic division of time conceals the fluidity of the boundaries between past, present and future. In many ways the past is here and will endure into the future for better or worse. As I write these lines, the New York Times (Nov. 29, 2022) writes about the friendly meeting between a former American president and a famous Holocaust denier, and, coincidentally, also publishes an interview with Tom Stoppard, the renowned playwright, focusing to a great extent on his Jewish heritage. Asked about antisemitism, which many would hope to see relegated to the past, but is stubbornly reemerging in different guises, Stoppard replied: “My own feeling is that marginal social attitudes never go away. They’re something like a latent virus that becomes activated under certain conditions.” And added: “The solution is to develop a society in which these issues barely arise because the society is fair. In many issues, I think, God, if only we could start education again from the bottom up. Just now begin with the next generation of 5-year-olds and teach them the philosophy of life.” Education, in other words, is one of the most important and most effective ways to deal with antisemitism, with Holocaust-denial and with so many other manifestations of extremism. While Stoppard obviously meant this in a very comprehensive and avowedly utopian way, the explicit study of the Holocaust in schools is as vital as ever.

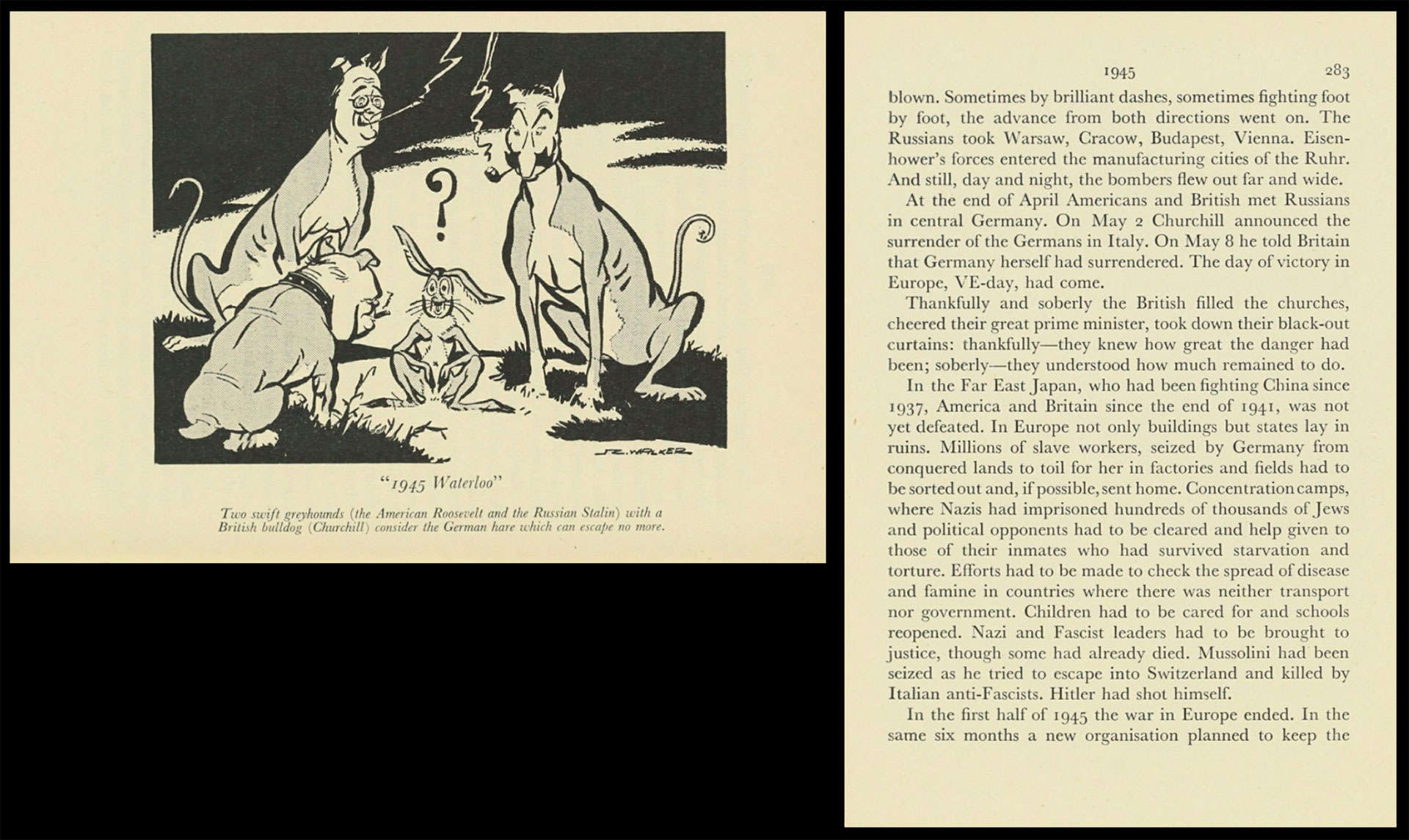

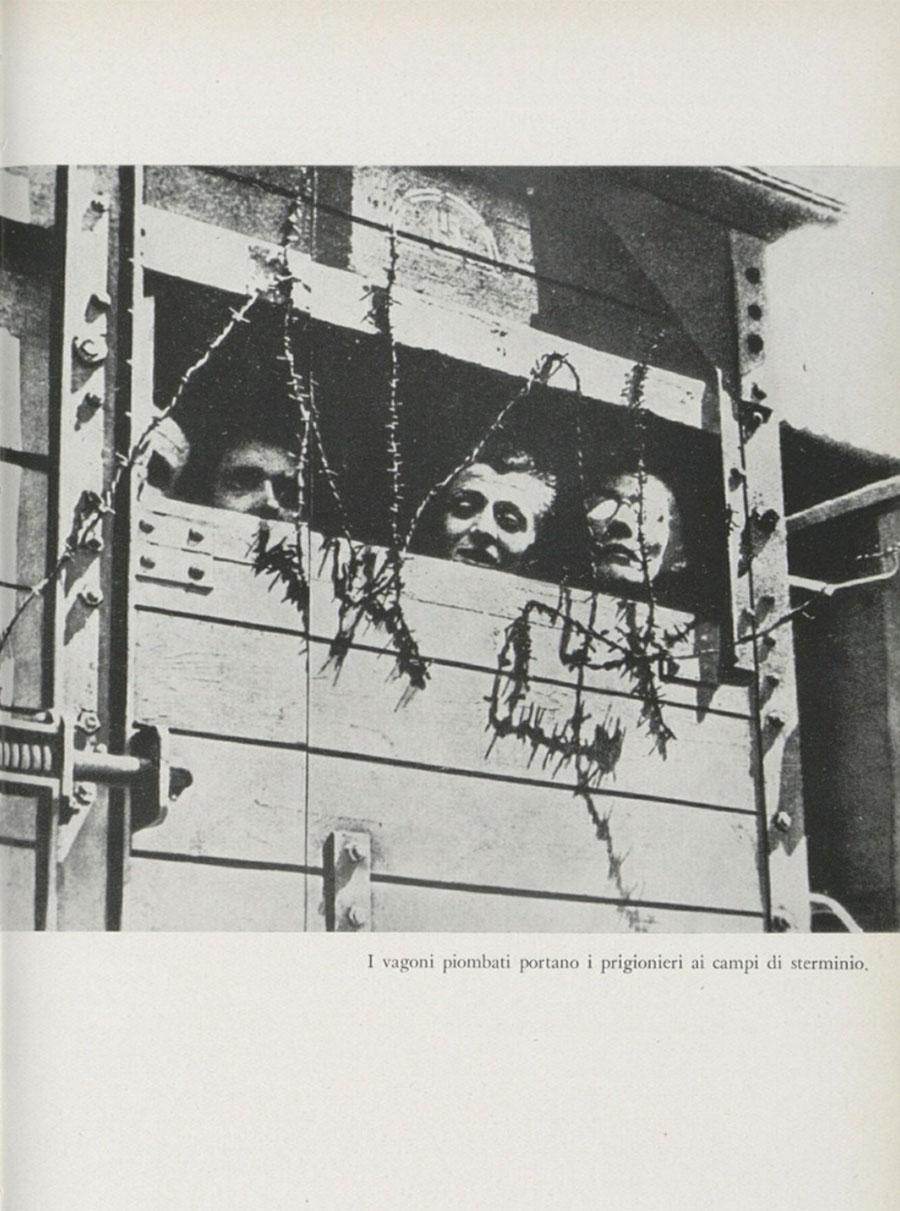

The case for this has been made in many recent studies, including in a book published under the aegis of the IBE, As the Witnesses Fall Silent: 21st Century Holocaust Education in Curiculum, Policy and Practice (edited by Z. Gross and E.D. Stevick; Springer 2015). Books by Eli Wiesel or Primo Levi, among others, are widely used in curricula across the world, and chapters on World War II in history textbooks often include long and detailed discussions of the Holocaust. If, however, we were to delve into the vast IBE collection of historical textbooks, we would discover, perhaps with some measure of perplexity, that it took quite a few decades before the Holocaust became a proper topic of debate and historical analysis in schools. We have surveyed here all the French, Belgian, Italian, British, American and Canadian textbooks available in the IBE digital collection. (This could well be used as a starting point for forays into other curricula – of the Soviet Union, of the two Germanies during the Cold War etc., which are likely to reveal many other interesting aspects.)